“A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.”

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Analyzing the connection between avant-garde and Marxism will help you understand how both aim for social change. This relationship continues to influence contemporary art, as many artists draw on Marxist ideas to address capitalism and social justice. Exploring this connection will deepen your appreciation of art’s role in society and its potential for inspiring transformative change. Bertolt Brecht, the influential German playwright and poet, emphasized the transformative power of art: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.”

What Is Avant-Garde?

Avant-garde is known for breaking away from traditional styles and experimenting with new ideas in art, music, and literature. It challenges established norms in how art looks and what it represents, often provoking thought and inspiring change. Avant-garde movements became prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially during social and political upheaval times.

What Is Marxism?

Based on the ideas of Karl Marx, Marxism focuses on the conflict between the wealthy and the working classes. Marxism encourages artists to address social issues, inequality, and class struggles. Artists influenced by Marxist ideas often use their work to highlight these issues and push for social change. Both avant-garde art and Marxism challenge established power and promote new ways of thinking.

What Appeared First?

Marxism appeared first. It was developed in the mid-19th century by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, particularly with the publication of The Communist Manifesto in 1848. Avant-garde art emerged later, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Artists began to challenge traditional art forms and societal norms, often influenced by revolutionary and anti-establishment ideas, including Marxist thought.

How and Why Are Avant-Garde and Marxism Connected?

Avant-garde and Marxism both challenge societal norms and advocate social change, which manifests in various ways.

Social Critique

Avant-garde art and Marxism are powerful tools for social critique. Avant-garde artists use their work to confront and challenge the dominant cultural narratives. They often highlight inequality, oppression, and societal norms that restrict individual freedom. This way, they provoke discussions around the structures perpetuating social injustices. Marxism complements this by analyzing the socioeconomic conditions that give rise to these injustices. It usually focuses on how capitalism creates and maintains class disparities. Avant-garde art and Marxism encourage audiences to rethink their perceptions of society and consider alternative futures.

Revolutionary Spirit

Avant-garde movements often arise during social and political upheaval periods. This is when artists feel a sense of urgency to break free from established artistic conventions to reflect the chaotic realities of their environment. This revolutionary spirit fits well with Marxist ideas, which call for getting rid of capitalist systems that exploit workers. Many avant-garde artists were influenced by Marxist thought. They used propaganda in art to promote radical ideas and encourage revolutionary action among their audiences. The call for artistic innovation is paralleled by the call for political and social revolution.

Focus on Class Struggle

Marxism focuses on the conflict between social classes resulting from economic inequalities. Many avant-garde artists, particularly during the early 20th century, recognized the importance of addressing class issues within their work. For example, movements like Dada and Socialist Realism represented the experiences of the working class and critiqued bourgeois values. These artists depicted the realities faced by everyday people, aligning their artistic practice with Marxist principles. Thus, avant-garde art serves as a critique of societal structures and a call for solidarity and collective action.

Experimentation and Innovation

Avant-garde art emphasizes experimentation and innovation. It pushes the boundaries of traditional forms and techniques, creating new modes of expression reflecting contemporary realities. This experimental approach allows artists to tackle complex social issues in ways that resonate more deeply with audiences. Similarly, Marxism encourages criticism of established norms and ideologies, promoting the idea that change is necessary for progress. The innovative nature of avant-garde art can effectively communicate Marxist themes by presenting them in fresh and engaging ways. It challenges viewers to rethink their understanding of social structures and their own roles within them.

Collective Identity

Both avant-garde movements and Marxist ideology put collective identity above individualism. Marxism posits that social change can only occur through the collective action of the working class uniting against oppressive systems. This sense of solidarity is mirrored in avant-garde art, where artists often collaborate and draw inspiration from each other. This helps to create works reflecting shared experiences and aspirations. They connect with their audience to make them see themselves as part of a larger movement for change. This collective identity reinforces the message that art can be a vehicle for social transformation, aligning closely with Marxist principles.

7 Avant-Garde Art Examples from History

Avant-Garde art was, in part, a response to the upheaval caused by World War I and later World War II. These wars prompted artists to experiment with new styles to express the chaos, trauma, and alienation of the modern world. This is how post-war art emerged.

Dada (1916–1924)

Context: Dada was a response to the devastation of World War I and the failure of traditional values that led to the war.

Example: Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917), a ready-made sculpture of a urinal, challenged the very definition of art. It rejected conventional aesthetics and hinted at the absurdity of the war and the futility of traditional artistic values.

Surrealism (1920s–1940s)

Context: Surrealism developed in the wake of World War I. It was influenced by the psychological theories of Sigmund Freud and a desire to explore the unconscious as a response to the chaos of the time.

Example: Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” (1931) features melting clocks in a dreamlike landscape. This work reflects the fluidity of time and reality. It challenges viewers to confront their perceptions and the impact of war on human consciousness.

Situationism (1950s–1970s)

Context: Situationism arose from the political and social turmoil of the 1960s, particularly in Europe. It critiqued consumer culture and aimed to encourage radical change in society.

Example: Guy Debord’s “The Society of the Spectacle” (1967) is a foundational text that critiques modern capitalism and media saturation. It presents the idea that images increasingly mediate social life, calling for a re-engagement with authentic experiences.

Fluxus (1960s)

Context: Fluxus was a response to the commercialization of art and the rigid structures of traditional artistic practices. It emphasized anti-art and the blurring of boundaries between art and everyday life.

Example: Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” (1964) involved the artist sitting silently on stage while audience members were invited to cut pieces of her clothing. This performance confronted issues of vulnerability, gender roles, and the commodification of the artist.

Postmodernism (1970s–1990s)

Context: Postmodernism arose as a reaction against the perceived limitations of modernism. It sought to address social issues such as identity, race, and gender in a fragmented society.

Example: Tarantino’s films, particularly Pulp Fiction (1994), are strong examples of postmodern cinema. His use of nonlinear storytelling, references to pop culture, genre mixing, and self-referential humor reflect postmodern techniques.

Black Arts Movement (1960s–1970s)

Context: This movement emerged as a response to the Civil Rights Movement and reflected African American identity and experience.

Example: Amiri Baraka’s poetry and visual art, such as “Black Art”, called for a new consciousness and solidarity among Black people.

Feminist Art Movement (1970s)

Context: In response to the feminist movement, artists sought to challenge traditional representations of women in art and society.

Example: Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1974–1979) is an installation that honors women throughout history. It uses a symbolic table setting to highlight their contributions and the erasure of their stories.

The Dark Side of Marxism’s Influence

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Orwell, G. (1945). Animal farm. Secker and Warburg.

The darker side of the Marxist influence on avant-garde art manifests under authoritarian regimes that claimed to follow Marxist principles. When communism came to power in the Soviet Union and China, Marxism’s revolutionary zeal was twisted into oppressive state control.

Soviet Union and Socialist Realism

After the Russian Revolution, avant-garde artists initially found a home within the Soviet regime, welcoming radical Marxist expressions. However, under Stalin, this changed drastically. Avant-garde art was seen as too individualistic and subversive. It led to the imposition of Socialist Realism as the official state art depicting idealized workers and glorified communist ideology. Social Realism stifled creativity and forced artists to conform to narrow ideological expectations. Those who resisted were often persecuted or silenced, with many avant-garde artists arrested or executed.

Censorship and Repression

In Maoist China, during the Cultural Revolution, the Marxist ideals led to extreme censorship and repression of artistic expression. Art was only valued if it served the state’s revolutionary goals so that any form of avant-garde, experimental, or critical art was forbidden. Intellectuals, artists, and cultural figures were often targeted, imprisoned, or killed for producing works that deviated from the state’s propaganda.

Loss of Artistic Freedom

The Marxist emphasis on collective over individual expression often resulted in a loss of artistic freedom. Avant-garde movements, which pushed boundaries and explored the unconventional, were suppressed under regimes that valued ideological purity over artistic innovation.

The Marxist Theory of Art

The Marxist theory of art developed from the broader Marxist framework established by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx did not write about art systematically but his ideas on economics, class struggle, and ideology were key for later art theorists. Over time, various thinkers, particularly in the 20th century, developed and applied Marxist ideas to art, culture, and aesthetics.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Foundations of the Theory

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels focused on the relationship between base (the economic structure) and superstructure (cultural, political, and ideological systems). They argued that the economic system shapes all aspects of society, including art, which is part of the superstructure.

- Karl Marx emphasized how the ruling class uses culture, including art, to maintain its control over society. Art can be used to reinforce existing power structures and ideologies. For example, the dominant classes often produce and promote art that upholds their interests, values, and worldview.

- Friedrich Engels also discussed how ideology, including art, serves the interests of the ruling class. However, he was more interested in how artists might contribute to revolutionary movements.

Marx and Engels did not formulate a comprehensive “Marxist theory of art.” However, their concepts of ideology, class struggle, and material conditions provided the theoretical foundation for later Marxist cultural theorists.

Key Figures in the Development of the Marxist Theory of Art:

- Georg Lukács (1885–1971): A Hungarian Marxist philosopher who was one of the earliest to apply Marxist theory to art. He believed that art should reflect historical materialism and show the alienation of workers under capitalism. Lukács argued that realism in art, which portrays the true nature of society and class struggle, could contribute to social change.

- Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937): An Italian Marxist theorist who developed the concept of hegemony. Gramsci argued that the ruling class maintains power not only through force but also by controlling cultural institutions, including art. He believed that revolutionary change would create new forms of art that represented their interests.

- Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956): A German playwright and theater director. Brecht played a key role in the development of Marxist aesthetics, particularly through his concept of epic theater. Brecht believed that theater should provoke critical thinking in the audience rather than merely entertaining them. He argued that art should expose the contradictions of capitalist society and promote political action.

The Frankfurt School and Cultural Marxism

In the mid-20th century, the Frankfurt School—a group of Marxist theorists based at the Institute for Social Research—developed a critical theory of culture, sometimes referred to as cultural Marxism. This group included theorists such as Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse.

The Frankfurt School theorists argued that culture, especially mass media, was a tool for the manipulation of consciousness. They believed that capitalism turned art into a product for consumption, thereby stifling its potential to promote social change. They called for a new form of art that would critique society and challenge capitalist ideology.

Implementing the Marxist Theory of Art

The implementation of the Marxist theory of art has often taken place in the form of:

- Revolutionary Art Movements: Throughout the 20th century, Marxist art movements emerged to challenge social structures and inequalities. These included the Dada movement, constructivism in Russia, and surrealism.

- Censorship and State Control: In certain Marxist regimes, particularly in the Soviet Union, art became heavily controlled by the state. The Soviet government enforced socialist realism to promote the ideology of the state. They limited artistic freedom in favor of producing art that supported the socialist cause.

Neo-Marxism and Critical Theory. Marxism Now

Neo-Marxism is a modern evolution of Marxist thought. It incorporates ideas from other schools, such as critical theory (popularized by the Frankfurt School) and elements of postcolonial theory. Neo-Marxists focus on systemic issues like cultural hegemony, global capitalism, and power dynamics.

Environmental Marxism

In the age of climate change, eco-socialism has emerged as a global movement merging Marxist critiques of capitalism with environmental activism. Eco-socialists argue that capitalist systems, driven by profit, are responsible for the exploitation of natural resources.

Global Protests Against Capitalism

Across the world, movements have emerged in response to rising economic inequality and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. While these movements don’t explicitly identify as Marxist, they criticize corporate power and the exploitation of labor.

Global Anti-Capitalism in Digital Spaces

Online communities and intellectuals engage in anti-capitalist discourse, often informed by Marxist critiques. These discussions frequently take place on social media and digital platforms, where activists and thinkers share critiques of global capitalism. They particularly analyze its role in increasing inequality, creating precarious labor conditions (gig economy), and contributing to global crises like pandemics and climate change.

Global South and Postcolonial Marxism

In many parts of the Global South, Marxist-inspired ideologies are reinterpreted through a postcolonial lens. Movements and governments in Venezuela, Cuba, and Bolivia have incorporated elements of socialism and Marxism in opposition to Western capitalist models. They focus on issues like imperialism, neocolonialism, and resource exploitation.

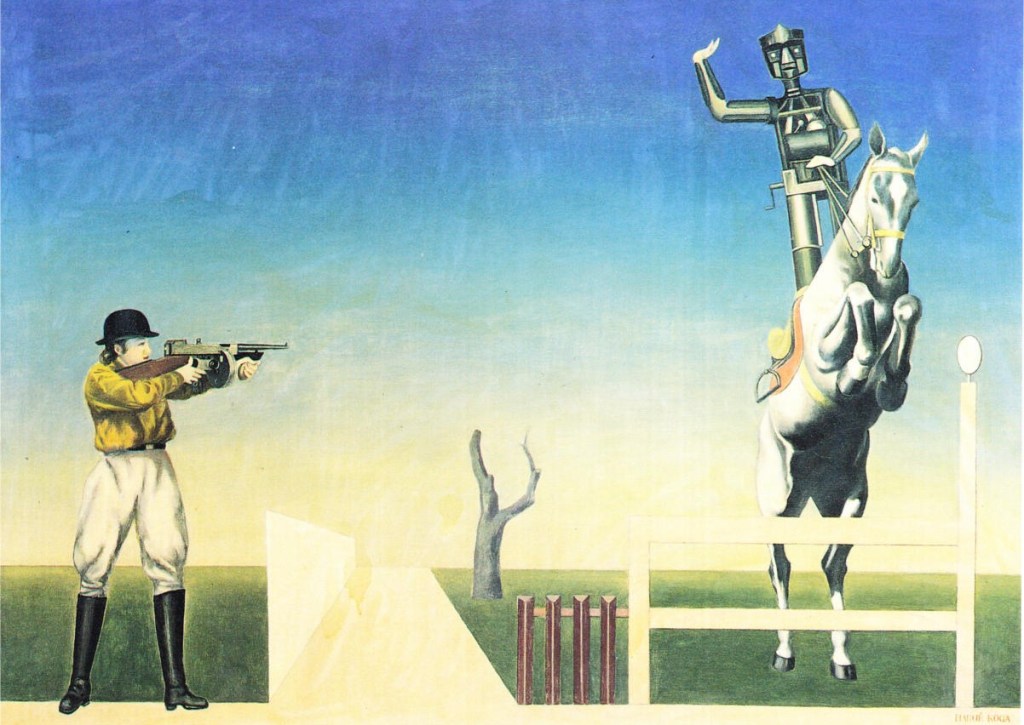

P.S. This painting was created by the Japanese avant-garde artist Harue Koga and is titled Intellectual Expression Traversing a Real Line (1931). It can be interpreted as Harue Koga’s reflection on the clash between modern technology and human life to critique industrialization and its impact on society.