Claude Monet’s Water Lilies series stands as one of the most ambitious and influential projects in the history of modern art. Comprising around 250 paintings created over the last thirty years of Monet’s life, the seriesis a lifelong meditation on perception, time, and experience. It is an attempt to paint not objects themselves, but the act of seeing and feeling the world.

The setting for this vast undertaking was Monet’s garden in Giverny, a small village in northern France where he settled in 1883. Over time, Monet transformed the property into a carefully constructed environment designed specifically for painting. He diverted a nearby river to create a pond, planted water lilies imported from different countries, built a Japanese-style wooden bridge, and surrounded the water with weeping willows, irises, bamboo, and other plants. Rather than a passive source of inspiration, the garden was an artwork in itself. Monet cared for it with the same attention and intention that he brought to his canvases.

At Giverny, Monet found a subject that could sustain endless variation. The water lily pond changed under the influence of light, weather, season, and time of day. Morning mist softened forms; midday light intensified color; evening shadows dissolved edges. Reflections of clouds, trees, and sky drifted across the surface of the water, merging with the lilies themselves. Monet became deeply absorbed in observing these shifts, often working on several canvases at once, switching between them as the light changed. This practice, which he had developed earlier in his series of paintings of haystacks and Rouen Cathedral, reached its most radical expression in the Water Lilies.

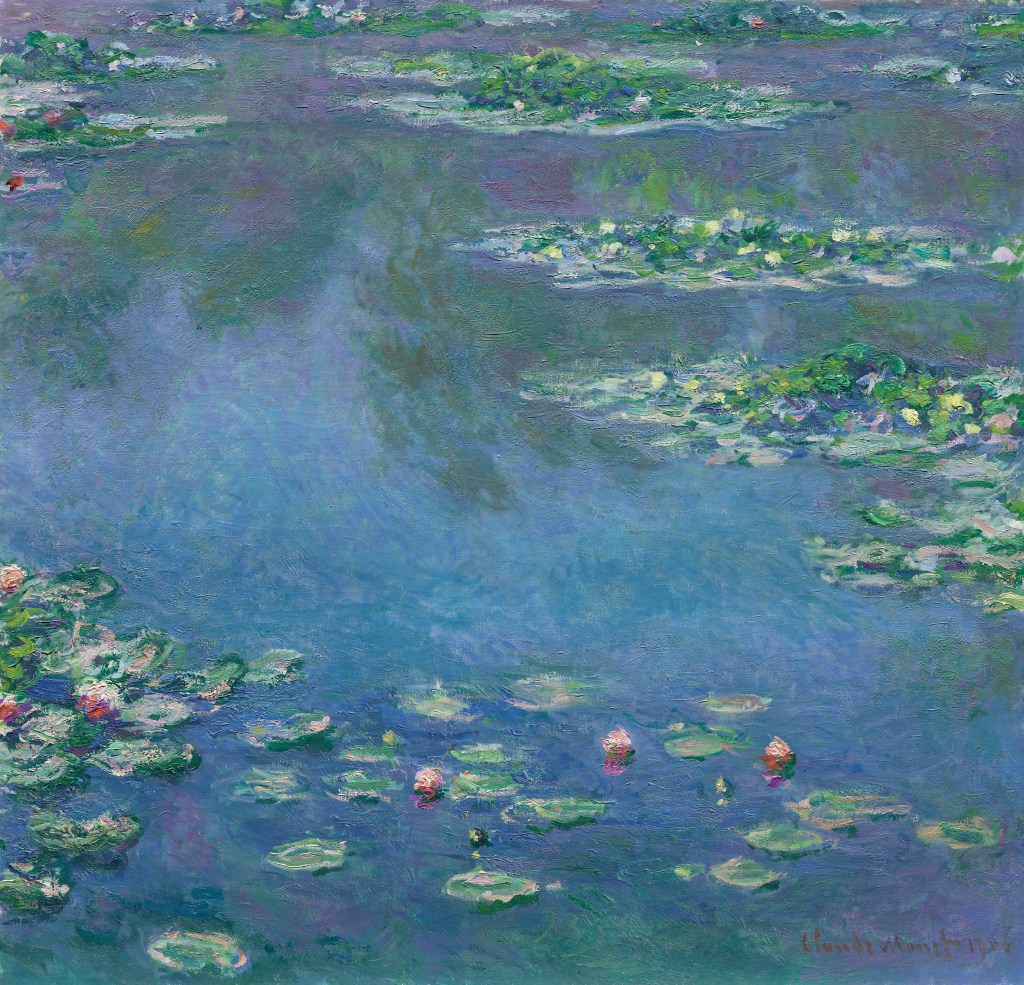

What makes these paintings so distinctive is their rejection of traditional composition. Many of the Water Lilies works have no horizon line, no clear foreground or background, and no fixed point of view. The viewer is not positioned at a distance, looking at a scene; instead, one seems to hover above the surface of the water, immersed within it. Space becomes ambiguous. Water reflects the sky, the sky dissolves into color, and solid forms lose their boundaries. This lack of stable perspective was highly unusual at the time and contributed to the sense that Monet was pushing painting toward abstraction.

Monet was not interested in botanical accuracy. The lilies are often suggested rather than precisely drawn, their shapes broken apart by ripples, reflections, and brushstrokes. What mattered to him was not how the flowers looked in isolation, but how they appeared within a constantly changing visual field. His brushwork became increasingly loose and fluid, especially in the later paintings. Strokes overlap, colors bleed into one another, and surfaces shimmer rather than define. The paint itself becomes a record of quick glances, shifting attention, and fleeting impressions.

Color plays a central role in conveying mood and atmosphere. Monet used subtle gradations of blues, greens, pinks, purples, and whites to suggest the movement of light across water. Rather than modeling forms with shadow, he relied on color relationships to create depth and vibration. In some paintings, cool tones dominate, creating a sense of calm or melancholy; in others, warmer hues introduce energy and intensity. These emotional variations were not imposed artificially but emerged from Monet’s close observation of his surroundings and his own sensory responses to them.

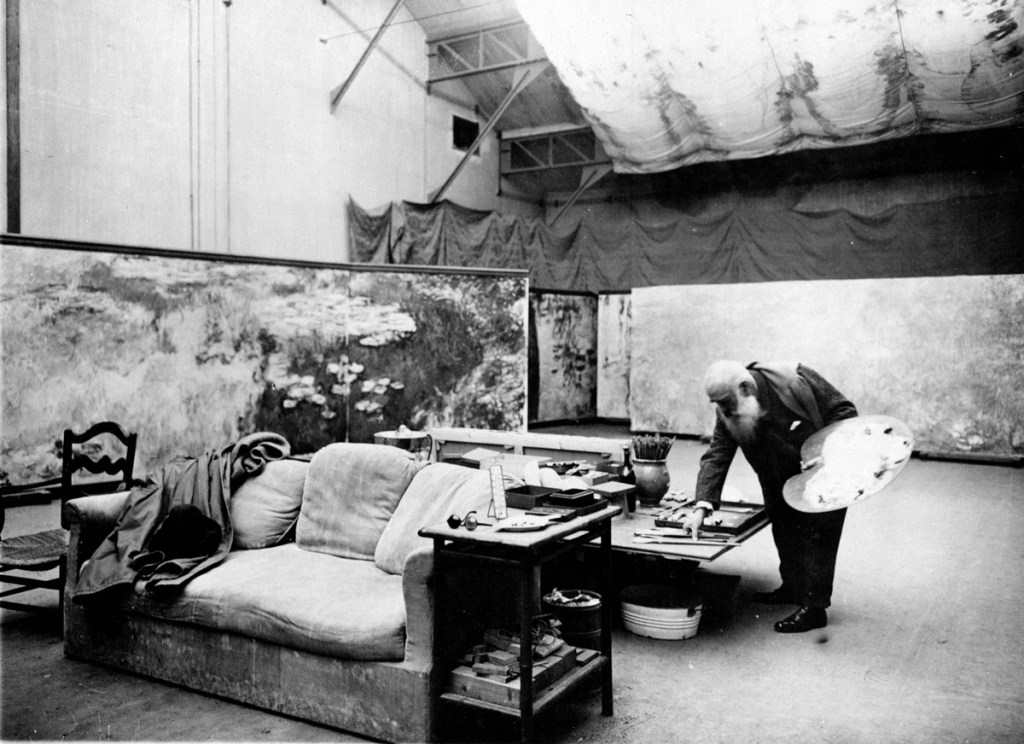

The scale of the Water Lilies project reached its culmination in the monumental decorative panels now housed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. Conceived as an immersive environment, these large canvases stretch across curved walls, surrounding the viewer with water, light, and color. Monet envisioned them as a space for contemplation, a place where visitors could experience a sense of peace and continuity. Installed after World War I, they were intended as a gesture of healing and renewal—a quiet counterpoint to the violence and fragmentation of the modern world.

These late works were created under difficult personal circumstances. Monet suffered from cataracts, which affected his vision and altered his perception of color. At times, his paintings became darker or more red-toned, reflecting both his impaired eyesight and his emotional state following the death of his wife and the upheaval of war. Yet even in these conditions, Monet continued to paint, driven by a deep commitment to his vision. After undergoing surgery late in life, he reworked some of the canvases, demonstrating his relentless pursuit of what he felt they needed to become.

The Water Lilies series had a profound influence on later generations of artists. Although Monet never identified as an abstract painter, his late works opened the door to abstraction by prioritizing sensation over representation. Artists associated with Abstract Expressionism, such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, later found inspiration in the immersive scale, all-over composition, and emotional intensity of Monet’s panels. In this sense, the Water Lilies form a bridge between Impressionism and modern abstract art.

It’s clear that Claude Monet’s Water Lilies are not about flowers or gardens alone. They are about time passing, light changing, and perception itself. Standing before these paintings, one does not simply observe a scene; one enters it. The absence of a fixed perspective invites the viewer to slow down, to drift, to feel. Monet sought to capture the sensation of being present in a moment that is always slipping away. In doing so, he created a body of work that remains deeply moving, quietly radical, and endlessly resonant.