Patterns are everywhere—in the curves of a shell, the petals of a flower, and even in the structure of great paintings. Two of the most famous patterns found in both nature and art are the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence. Though based on mathematics, they often appear where no ruler or equation was ever used.

The golden ratio, approximately 1.618, describes a proportion where the whole is to the larger part as the larger part is to the smaller. It’s a simple idea, but it appears in everything from ancient temples to modern logos.

What Is the Golden Ratio?

The golden ratio, often represented by the Greek letter φ (phi), is a mathematical constant that appears when a line is divided so that the ratio of the whole line to the longer segment is the same as the ratio of the longer segment to the shorter one. This ratio is approximately 1.6180339887.

The golden ratio is an irrational number—meaning it can’t be expressed as a simple fraction. It has fascinated mathematicians and artists since ancient times. The Greek philosopher Euclid described it in his work Elements around 300 BCE, calling it the “extreme and mean ratio.”

Mathematically: (a + b)/a = a/b = φ

This proportion has measurable appearances in aesthetics, geometry, and growth patterns.

The Fibonacci Sequence Approaching the Golden Ratio

The Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34…

It was introduced to the West by Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci, in his 1202 book Liber Abaci. The book used this sequence to solve a problem about rabbit populations, but the numbers themselves turned out to be far more significant.

As the sequence continues, the ratio of two successive Fibonacci numbers converges to the golden Ratio: 21/13 ≈ 1.615, 34/21 ≈ 1.619, and so on.

This convergence is not a coincidence. Mathematically, the golden ratio is the limit of the ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers.

The Golden Ratio in Art and Architecture

The golden ratio has been used in works of architecture and art with documented intent, especially during the Renaissance. The clearest examples include:

Leonardo da Vinci worked closely with mathematician Luca Pacioli, who published De Divina Proportione in 1509. This book explored the golden ratio’s role in art and geometry, and da Vinci provided the illustrations.

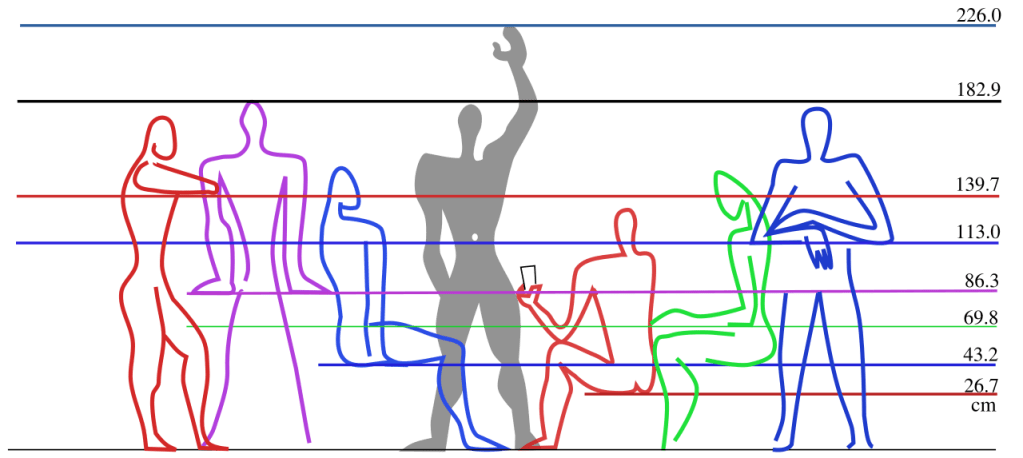

Le Corbusier, a 20th-century architect, developed the Modulor system—based on the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence—to standardize human-scaled proportions in his buildings.

Salvador Dalí is said to have used a golden rectangle as the base structure for The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955). He structured the canvas of this painting as a golden rectangle, and the dimensions of the central space and the dodecahedron above Christ’s head reflect φ proportions. Dalí was deeply interested in mathematics and mysticism and explicitly stated that the golden ratio influenced the structure of this composition.

Mario Livio, a well-known astrophysicist and author of The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, offers one of the most rigorous modern examinations of how the golden ratio manifests in Salvador Dalí’s The Sacrament of the Last Supper. Livio points out that the canvas itself, measuring 267 × 166.7 cm, has proportions very close to a golden rectangle, suggesting that Dalí deliberately chose its dimensions to approximate φ. Beyond the frame, Livio highlights the enormous transparent dodecahedron that envelops the supper scene: this twelve-faced Platonic solid is deeply connected to φ, since the pentagonal faces of a regular dodecahedron are geometrically tied to the golden ratio. Livio interprets this structure not just as a mathematical flourish, but as a symbol of cosmic and spiritual order. Dalí himself described the dodecahedron in terms of the “celestial communion of the number twelve.” In Livio’s view, Dalí’s integration of φ wasn’t a superficial nod to a “beautiful” proportion, but an intentional fusion of mathematics, faith, and metaphysics.

Examples of the Fibonacci Sequence in Nature

The Fibonacci sequence shows up in various biological systems—not as a law of nature, but as a recurring pattern. It is most evident in phyllotaxis, the arrangement of leaves, petals, or seeds on a plant stem. Many plants place new growth at angles that approximate the golden angle: 137.5°, which optimizes sunlight exposure and packing efficiency.

A few confirmed examples:

Sunflowers: The spiral arrangement of seeds often follows Fibonacci numbers like 34 and 55, or 89 and 144.

Pine cones and pineapples: The scales are arranged in intersecting spirals of Fibonacci-numbered counts.

Daisy petals: Commonly occur in Fibonacci numbers such as 21, 34, or 55.

Romanesco broccoli: Shows fractal growth that mimics the sequence geometrically.

The Nautilus Pompilius: A Misunderstood Icon

The shell of the marine mollusk Nautilus pompilius is frequently described as a “perfect” golden spiral. A logarithmic spiral is a curve that winds around a center point and expands at a constant rate. While it does grow in a logarithmic spiral, it does not match the golden spiral precisely.

Still, some studies proposed that while the nautilus follows a logarithmic growth pattern, the spiral expands at a ratio closer to 1.33, not 1.618. Earlier research by mathematician Clement Falbo found similar results, with ratios ranging from 1.24 to 1.43.

Despite this, the nautilus has become a visual shorthand for natural harmony and proportion. Artists and designers still use its form as a reference, understanding that in art, symbolism often matters more than mathematical precision.

What the Golden Ratio Isn’t

Although the golden ratio has many real applications, not all claims about it are true. Some commonly repeated myths include:

- That all human faces rated as beautiful fit into golden rectangles—scientific studies have shown no consistent correlation.

- That all famous artworks were constructed with φ grids—many are simply well-balanced by the artist’s intuition.

In his book The Seven Mysteries Of Life: An Exploration of Science and Philosophy, Guy Murchie wrote: “The Fibonacci Sequence turns out to be the key to understanding how nature designs… and is… a part of the same ubiquitous music of the spheres that builds harmony into atoms, molecules, crystals, shells, suns and galaxies and makes the Universe sing.”

A Math Producing Beauty

The golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence are not magic; they’re mathematical patterns that appear often because they solve real-world problems efficiently. In art, architecture, nature, and design, they offer structure, balance, and a link between intellect and instinct. Hence, Leonardo da Vinci, Dalí, and Le Corbusier used φ because it worked.