Among the many movements that have shaped the art world, Impressionism and Expressionism stand out for their unique approaches to conveying reality. While both movements emerged as reactions against the established norms of their times, they diverged significantly in their techniques, subjects, and underlying philosophies.

Expression vs. Impression

The names “Impressionism” and “Expressionism” come directly from the ideas each movement emphasized, and each has an interesting story behind it.

Impressionism got its name from a critic’s sarcastic remark. In 1874, Claude Monet exhibited a painting titledImpression, Sunrise (Impression, Soleil Levant in French). A journalist used the word “impression” to mock the work, saying it looked unfinished and was just an “impression” of a scene rather than a detailed painting. The artists decided to embrace the term, and this is why Impressionism is called that way. For them, an “impression” meant capturing a fleeting moment, the visual sensation of a scene as it appeared to the eye, especially under changing light conditions. It reflected their focus on immediate perception rather than perfect realism. So, the name literally points to their goal: showing the impression of a moment.

Expressionism is named for its focus on expressing inner emotions. Unlike Impressionists, Expressionists were not concerned with light or the accurate depiction of the external world. Instead, they wanted their art to convey feelings, such as fear, anxiety, passion, or ecstasy. The term “expression” highlights that the painting is less about what the eye sees and more about what the mind or soul experiences. German artists in the early 20th century, such as those in Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, employed exaggerated forms, intense colors, and distorted perspectives to render the inner world visible.

In short, Impressionism is about what the eye perceives; Expressionism is about what the heart and mind feel. The names are literal clues to each movement’s purpose.

Which Came First?

Impressionism emerged in France during the 1860s–1870s as a rebellion against the academic painting that dominated the Paris Salon. Academic art prized mythological or historical subjects, smooth brushwork, and polished realism. But the younger painters wanted to capture modern life and the way we actually see.

They painted en plein air (outdoors), using quick brushstrokes and bright colors to show fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. The industrial revolution also played a role: new paint tubes made outdoor painting easier, and urbanization gave them new subjects like cafés, railways, and city streets.

Expressionism arose later, around 1905–1910, mainly in Germany and Austria, though its roots spread wider. By then, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism had already reshaped European art.

Impressionism had broken with the strict academic tradition. This opened the door for later artists to explore even more radical directions. But while Impressionism focused on the external world and optical effects, Expressionism reacted against that. Expressionists felt Impressionism showed surfaces, not depths. It captured how the world looked, but not how it felt.

Think of it this way: Impressionism asked, “How does light fall on this object at this moment?” Expressionism asked, “What emotional truth does this object awaken in me?”

The Link Between Impressionism and Expressionism

The connection between the two is not about similarity, but about artistic freedom. Without Impressionism, Expressionism may not have been possible. Impressionism broke rules. By ignoring academic standards, Impressionists made it acceptable for artists to paint in personal, subjective ways. Post-Impressionism took it further. Painters like Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne transformed Impressionist methods into new directions: Van Gogh with emotional intensity, Gauguin with symbolic color, Cézanne with structural experimentation. Expressionists later looked especially to Van Gogh, whose swirling, emotionally charged brushwork felt closer to their own aims than Monet’s calm light studies. Expressionism radicalized the subjectivity. Instead of capturing fleeting impressions of the outer world, Expressionists used exaggeration, distortion, and intense color to communicate inner feelings like angst, ecstasy, alienation, and desire.

So, Expressionism can be seen as a response to Impressionism’s limits. Impressionism freed painting from rigid tradition, but Expressionism declared that instead of simply depicting the world, a painting should show how it feels inside the human being.

Seeing the World vs. Feeling It

Although Impressionism and Expressionism both broke with tradition, their features and goals could not be more different. Impressionism was concerned with the outer world, the visible surface of things. Expressionism shifted attention inward, into emotion and imagination.

Impressionist paintings often seem light, shimmering, and spontaneous. The artists painted quickly, using short, visible brushstrokes that suggested movement rather than fixed form. Their palettes were bright, with a preference for pure, unmixed colors placed side by side to create optical effects. Shadows were rarely black; instead, they contained subtle mixtures of color reflecting the surrounding light. The subject matter was everyday life: gardens, rivers, boulevards, cafés, or dancers on stage. The aim was not to tell a story but to capture the sensation of a moment in time. A viewer standing before Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette (1876) feels as though sunlight dances across the crowd, filtered through the leaves of the trees. The painting is a lively impression of a moment in time rather than a detailed portrait of every figure. This “impression” is rendered through loose, shimmering brushstrokes and a vibrant play of light and shadow.

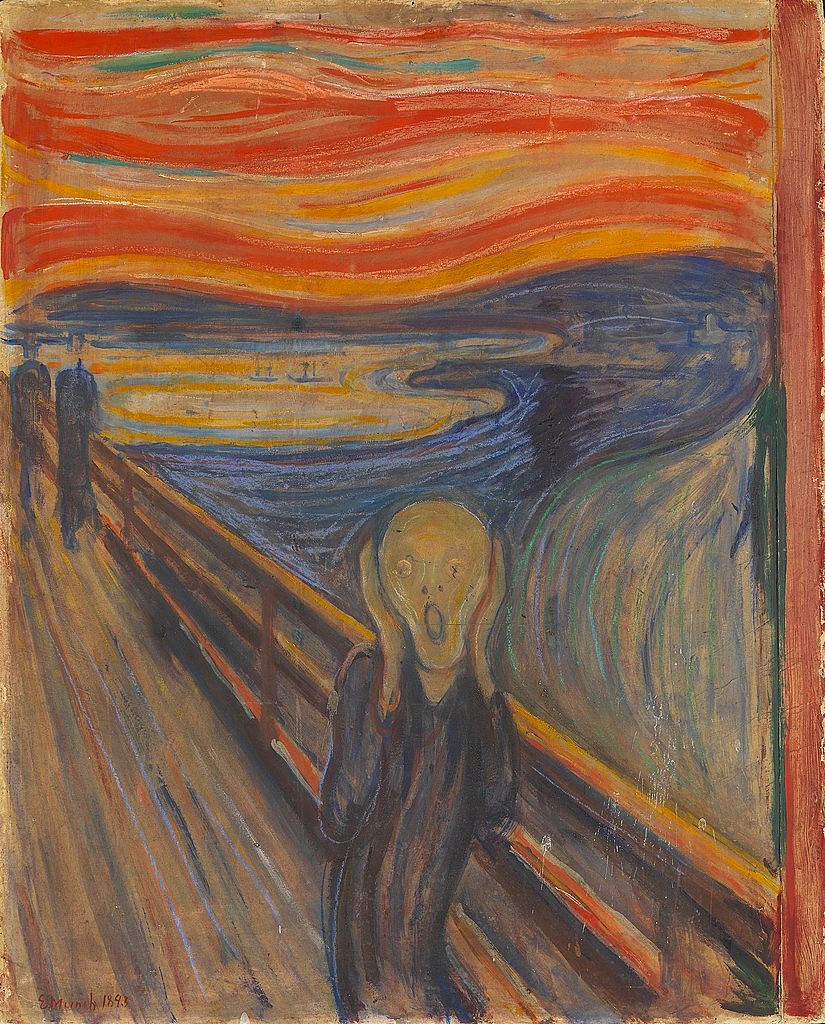

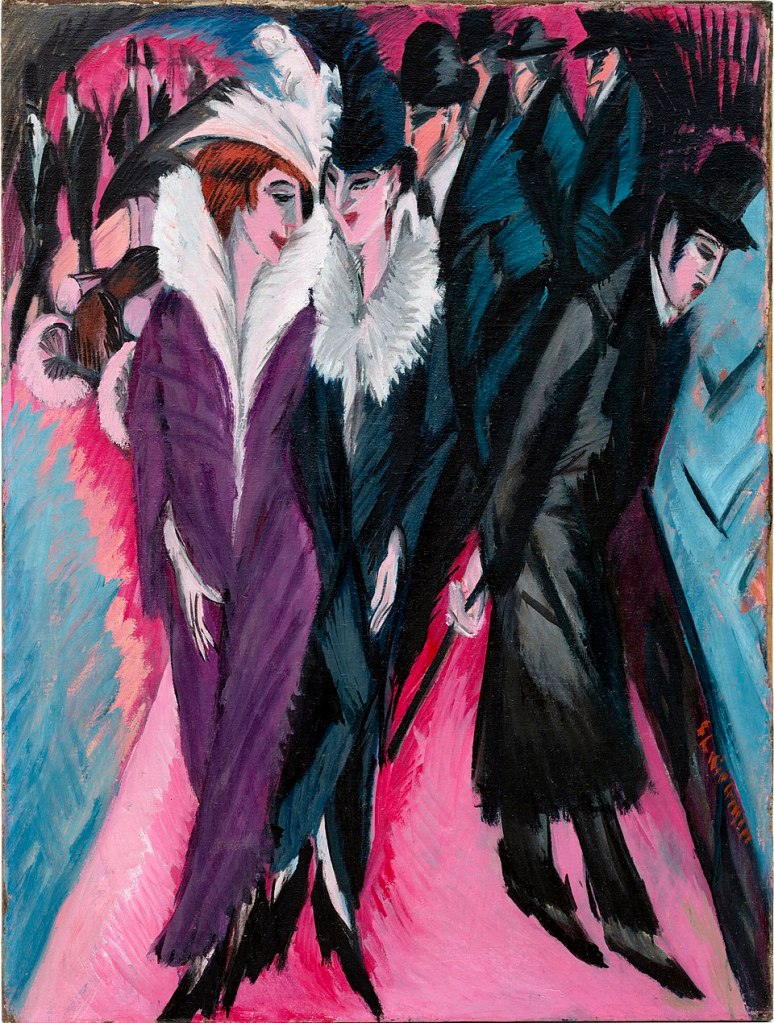

Expressionism, by contrast, presents a completely different mood. Its colors are intense and often unnatural, such as electric blues, blood reds, and acidic yellows. Forms are distorted, stretched, or exaggerated, creating tension and unease. Brushstrokes can be violent, jagged, or heavily layered, as if the painter was struggling with the canvas. The subject matter ranges from portraits to city scenes, but is always transformed by emotion. The anxiety in Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) is conveyed through a trembling silhouette, while the sky twists into a terrifying swirl of orange and red. The work does not describe a place but a psychological state, an existential cry given visual form. Similarly, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s street scenes of Berlin distort human figures into sharp angles and mask-like faces, embodying alienation rather than joy.

The differences become even clearer when you imagine both movements treating the same theme. An Impressionist painting of a city might show light glittering on wet pavement, figures blurred as if in motion, the air alive with fleeting atmosphere as in Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877). An Expressionist city scene, however, compresses the space and fills it with clashing colors, creating unease in works such as Kirchner’s Street, Berlin (1913). One celebrates sensory perception; the other exposes psychological tension.

Technically, Impressionists relied on open compositions and left parts of the canvas less defined, suggesting rather than fully describing. Expressionists often used closed, heavy compositions, crowding figures or landscapes to heighten drama. Where Impressionism feels airy and open to change, Expressionism feels urgent, charged, and at times claustrophobic.

This contrast reflects their underlying philosophies. Impressionism believes truth lies in careful observation of the external world at a particular instant. Expressionism believes truth lies in subjective experience, in revealing the invisible emotions beneath the surface. Together, they represent two radically different answers to the same artistic question: should art reflect the world as we see it, or as we feel it?

What Came Next?

After Expressionism, several different modern movements took shape in the 1910s and 1920s. Some were direct reactions to Expressionism, while others developed in parallel. A few of the most important ones include the following.

Dada (1916–1920s)

Born during World War I in Zurich, Dada was anti-art, rejecting logic, beauty, and traditional meaning. Artists like Hugo Ball and Marcel Duchamp used absurdity, chance, and provocation to protest a world that had descended into war. In a way, it was the opposite of Expressionism: instead of pouring out raw emotions, Dada mocked the very idea of meaning.

Surrealism (1920s–1930s)

Emerging in Paris, Surrealism built on Dada’s rebellion but turned toward psychology. Influenced by Freud, Surrealists like Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte explored dreams, the unconscious, and irrational imagery. Where Expressionism distorted reality to express feelings, Surrealism distorted reality to explore the hidden mind.

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity, mid-1920s)

In Germany, after Expressionism’s intensity, some artists returned to a cooler, more realistic style. Painters like Otto Dix and George Grosz exposed social inequality, corruption, and postwar trauma through sharp, unforgiving realism. It was almost a corrective to Expressionism, focusing less on inner turmoil and more on harsh external realities.

Abstract movements

By pushing color, form, and gesture away from strict representation, Expressionism opened the door to more radical experiments. This spirit carried into Abstract Expressionism, which took shape in New York in the 1940s and 1950s with artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman.

So, Expressionism wasn’t replaced by a single “next” movement—it branched out. Some artists turned to absurdity (Dada), others to dreams (Surrealism), others to realism (Neue Sachlichkeit), and some to abstraction. But Expressionism’s focus on inner truth remained a powerful influence, especially later in Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s and 1950s in the United States.

Expressionism and Abstract Expressionism

Expressionism began in Germany and Austria around 1905–1914. Its central idea was that art should not copy external reality but should express inner truths. Painters like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Egon Schiele twisted forms and used violent color to convey states of mind. Kandinsky, part of Der Blaue Reiter, took this further: for him, color and form alone could carry spiritual and emotional meaning. By 1913, he was painting almost fully abstract works, proving that Expressionism could move beyond figuration.

War, Exile, and Suppression

World War I and its aftermath fractured the Expressionist groups. Some artists, disillusioned, turned to realism (Neue Sachlichkeit). Others continued to experiment with more abstract and symbolic forms. But the rise of the Nazi regime in the 1930s silenced Expressionism in Germany. The Nazis labeled it “degenerate art” and banned its exhibition. Many Expressionist painters fled Europe, carrying their ideas abroad, while others were forced into isolation. This suppression ironically helped spread Expressionist influence beyond Germany, as the movement’s works and ideas circulated in new contexts.

Across the Atlantic

In the 1930s and 1940s, New York became a gathering place for émigré European artists escaping fascism and war. Figures like Piet Mondrian, Josef Albers, and Marcel Duchamp. American painters absorbed their lessons. Kandinsky’s writings, especially Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), were widely read and deeply shaped a younger generation of American artists. His belief that abstract forms could communicate profound emotions became a cornerstone for what was to come.

At the same time, American artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman were searching for a new language of painting. They were influenced by Surrealism’s focus on the unconscious, but also by Expressionism’s idea that painting could be a direct channel for inner states.

Abstract Expressionism

By the mid-1940s, this mix gave birth to Abstract Expressionism in New York. The movement kept Expressionism’s emotional intensity but abandoned recognizable subject matter. Instead, the canvas itself became a field of action or meditation. Pollock’s drip paintings transformed brushwork into pure movement, echoing Expressionist urgency but on a monumental scale. Rothko’s color fields used vast, glowing rectangles of color to evoke quiet, spiritual moods, a continuation of Kandinsky’s belief in color as emotion. de Kooning’s abstractions preserved figural traces but twisted them almost beyond recognition, much like German Expressionists had done.

Critics called it “Action Painting” or “The New York School,” but the label Abstract Expressionism stuck, acknowledging the lineage back to European Expressionism.

The Line of Continuity

So the connection is not linear in style, but in spirit. Expressionism said: art must express the inner life of the artist. Abstract Expressionism carried that conviction into a new era, with larger canvases, bolder gestures, and total abstraction. Where the German Expressionists expressed angst in distorted figures, the Americans expressed it in the very act of painting itself.

Without Expressionism’s break from realism and its insistence on subjective truth, Abstract Expressionism could not have taken shape. In a sense, the story is one of migration: an idea born in Germany, suppressed in Europe, then reborn in postwar America, where it defined the first globally influential American art movement.

So, art is never just about technique or style; it is a mirror of human perception and emotion. Impressionism and both Expressionism and Abstract Expressionism remind us that there are many ways to experience the world—through the eye, through the heart, and sometimes through both.