On the edge of the Black Sea, where the horizon is often silver with mist and the air smells of salt and citrus, two giant figures rise from the promenade. Every evening, they begin their slow dance: approaching, merging, and parting again. This is Ali and Nino, one of the most poetic landmarks of modern Georgia, a kinetic sculpture that tells a story of love, loss, and the invisible borders between people.

The Story of Ali and Nino

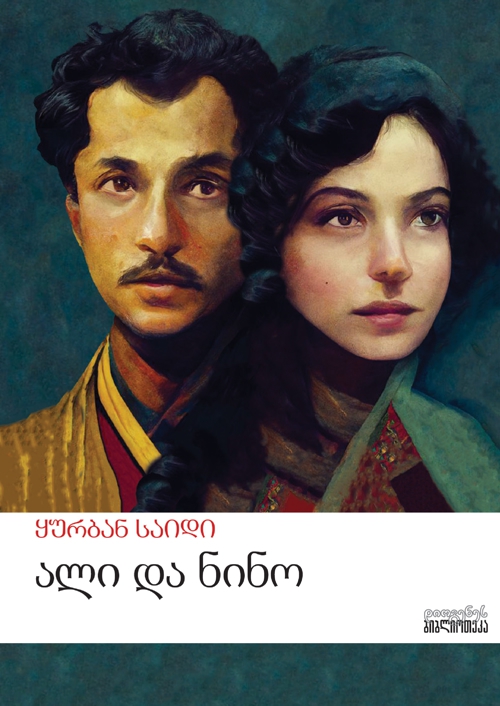

The sculpture takes its name and spirit from Ali and Nino, a 1937 novel attributed to Kurban Said. Set in the early 20th century in the Caucasus, a region balanced between Europe and Asia, the story follows a Muslim Azerbaijani man and a Christian Georgian woman who fall in love while their worlds tilt under the pressure of politics, religion, and war.

The novel is often described as a Caucasian Romeo and Juliet, but that comparison misses its particular soul. It’s not just about forbidden love, but also about the fragility of identity in a land that has always been a meeting point of cultures. The atmosphere of Ali and Nino is both romantic and tragic: it’s filled with desert winds, mountain light, and the tension between faith and freedom.

When Georgian artist Tamara Kvesitadze encountered this story, she saw in it a striking metaphor for movement. Her sculpture, created in 2010 and installed in Batumi shortly after, transforms the novel’s silent ache into something visible and rhythmic.

Why Batumi?

Batumi, Georgia’s seaside capital, is unlike any other city in the Caucasus. Once a sleepy Black Sea port, it has grown into a lively mosaic of glass towers, palm-lined boulevards, and faded Belle Époque architecture. The city’s skyline mixes Ottoman and European influences, echoing the same cultural crossings that shaped Ali and Nino.

Placing the sculpture here wasn’t accidental. Batumi’s seafront faces west, toward sunset, and the horizon becomes part of the installation. The two figures stand near the water, their steel bodies glowing against the shifting light, as if they belong to both land and sea. The setting captures the idea that love, like the tide, moves in cycles: advancing, retreating, and returning endlessly.

About the Artist, Tamara Kvesitadze

Tamara Kvesitadze (b. 1968, Tbilisi) began her career as an architect before turning to sculpture, installation, and kinetic art. Her work often blends mechanical precision with emotional depth. She explores how form, movement, and time can express what words cannot.

Her sculptures are rarely static. Instead, they breathe, unfold, or transform, reflecting her fascination with the line between the animate and the inanimate. Kvesitadze’s works have appeared at major exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale, where Man and Woman (the original title of Ali and Nino) first appeared. In Batumi, she found a home for the piece that matched its spirit.

How the Magic Works

Unlike traditional sculptures that remain still, a kinetic sculpture is designed to move, either through mechanical systems, natural forces like wind, or the viewer’s interaction. The word kinetic comes from the Greek kinesis, meaning “movement.” In art, it describes works that incorporate motion as a fundamental element rather than a decorative effect.

The concept emerged in the early 20th century, with artists like Naum Gabo and Alexander Calder experimenting with movement to challenge the static nature of sculpture. They believed that motion could express the energy and impermanence of modern life, the way forms shift, evolve, and dissolve over time. Tamara Kvesitadze’s Ali and Nino belongs to this lineage, yet it carries a distinctly emotional dimension. Here, movement isn’t only visual; it’s narrative.

Standing about eight meters tall, each figure is built from dozens of horizontal steel segments that rotate on a central axis. From a distance, they appear as translucent silhouettes. Slowly, they begin to glide toward each other.

Over the course of roughly eight minutes, the slices align, and the two figures overlap, becoming one. For a brief, breathtaking moment, they seem to embrace, and then continue past each other, dissolving into separate forms again. The motion repeats in an endless loop.

The choreography is simple but profoundly moving. The mechanism beneath, a precise system of motors and programming, remains invisible, allowing the focus to stay on the emotional rhythm. It is a meeting and a parting, a cycle of connection and loss. Viewers often describe it as hypnotic: the kind of beauty that’s both mechanical and human at once.

A Symbol of Persistence

In a city known for its mix of old-world charm and new ambition, Ali and Nino has become a reminder of never-ending contradictions—faith and reason, permanence and change.

Ali and Nino never stay together, but they never stop trying. In their endless dance, they show what it means to love in a world of distance: the beauty of approach, the sadness of passage, and the quiet strength of continuing anyway.