Cubism challenges the idea that the world can be seen from a single viewpoint. Artists fragment objects into planes and reassemble them to show multiple perspectives at once. The movement emerged in Paris around 1907, led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Space becomes shallow, analytical, and constructed rather than illusionistic. Influenced by Cézanne, African sculpture, and modern science, Cubism treats reality as something to be understood, not imitated. It developed from early Analytic Cubism to later Synthetic Cubism, which introduced collage and everyday materials. Form and structure replace narrative and emotion as the core concerns.

Cubist Art Gallery

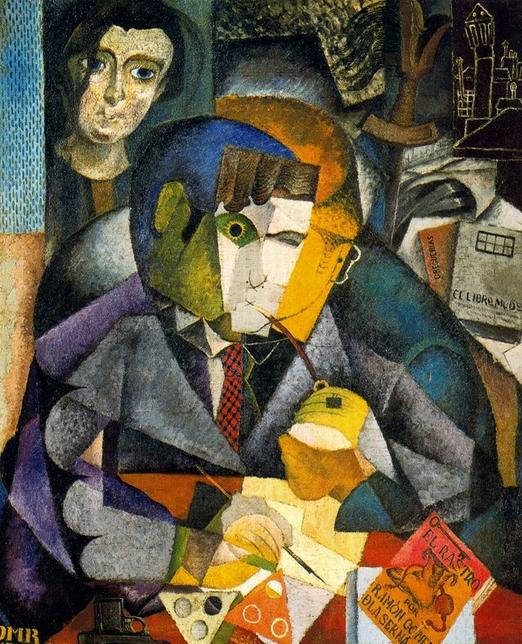

Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna (1915) by Diego Rivera

Rivera breaks the sitter into angular planes that suggest thought and movement rather than likeness. The portrait emphasizes intellectual presence over physical realism. Influenced by European Cubism, the work shows Rivera’s engagement with modern theory before his later political murals. Identity here feels constructed, not fixed.

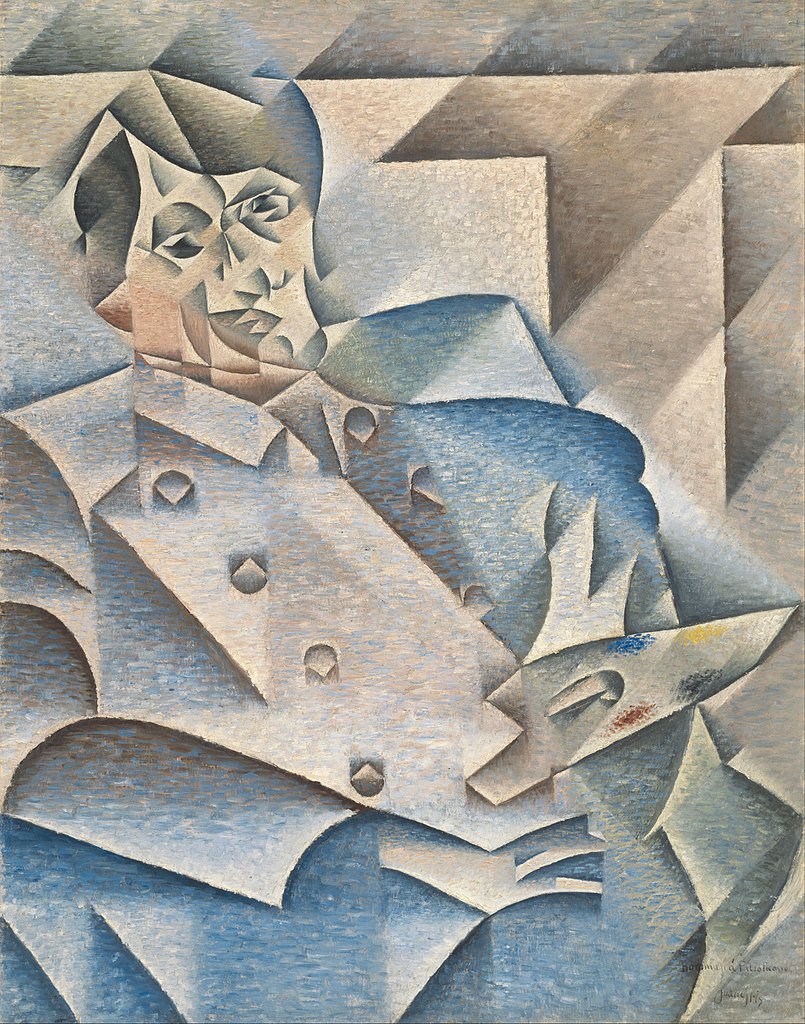

Portrait of Pablo Picasso (1912) by Juan Gris

Gris presents Picasso through tightly organized geometric forms. The palette stays restrained, reinforcing structure over personality. Unlike the more radical fragmentation of early Cubism, this portrait feels measured and deliberate. It treats Cubism as a system rather than an experiment.

Artillery (1911) by Roger de la Fresnaye

Military machinery appears broken into bold, colorful shapes. Despite the subject, the tone feels energetic rather than tragic. La Fresnaye balances modern warfare with visual clarity and rhythm. The painting turns conflict into a formal problem of movement and structure.

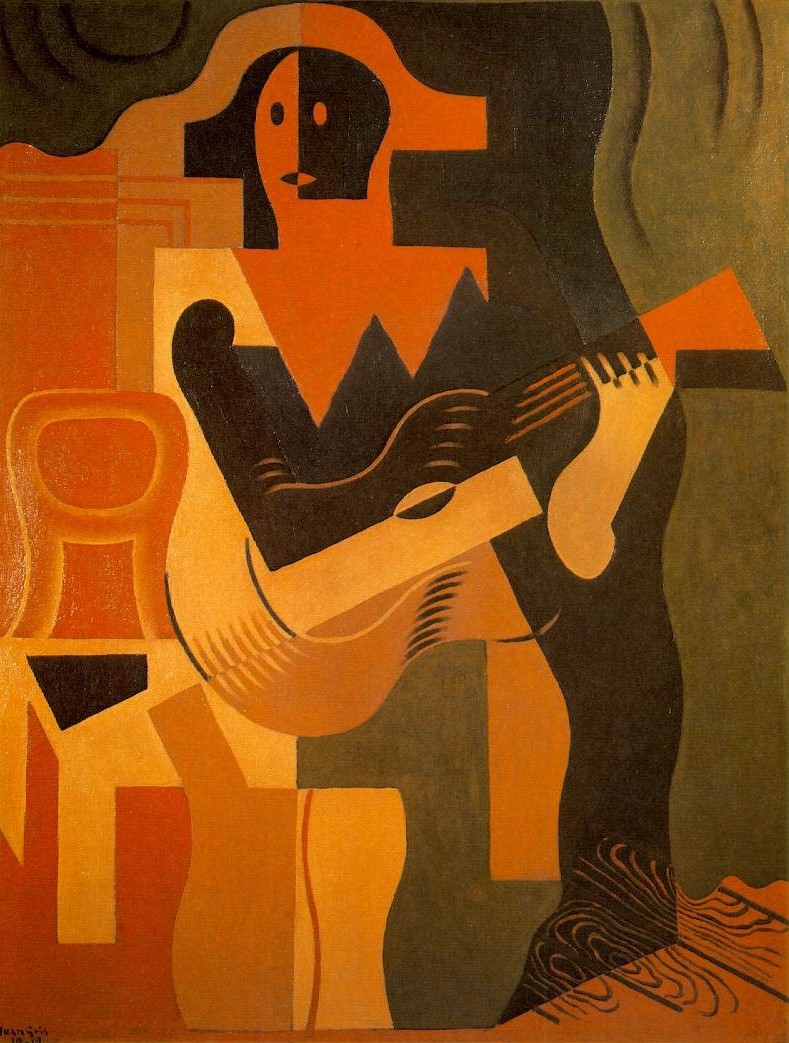

Harlequin with Guitar (1919) by Juan Gris

The familiar Cubist motif of the harlequin becomes calm and architectural. Clear outlines and layered planes create stability instead of fragmentation. Gris favors harmony and legibility over chaos. Music, performance, and structure quietly merge.

Conquest of the Air (1913) by Roger de la Fresnaye

This work celebrates technological progress through dynamic composition. Airplanes, figures, and symbols interlock like parts of a machine. Cubist geometry conveys speed and optimism rather than disorientation. Modernity appears heroic and forward-looking.

Man on a Balcony (1912) by Robert Delaunay

The figure dissolves into color and rhythm, almost merging with the city around him. Traditional Cubist browns give way to bright hues. The painting explores movement and urban energy rather than solid form. Vision itself becomes the subject.

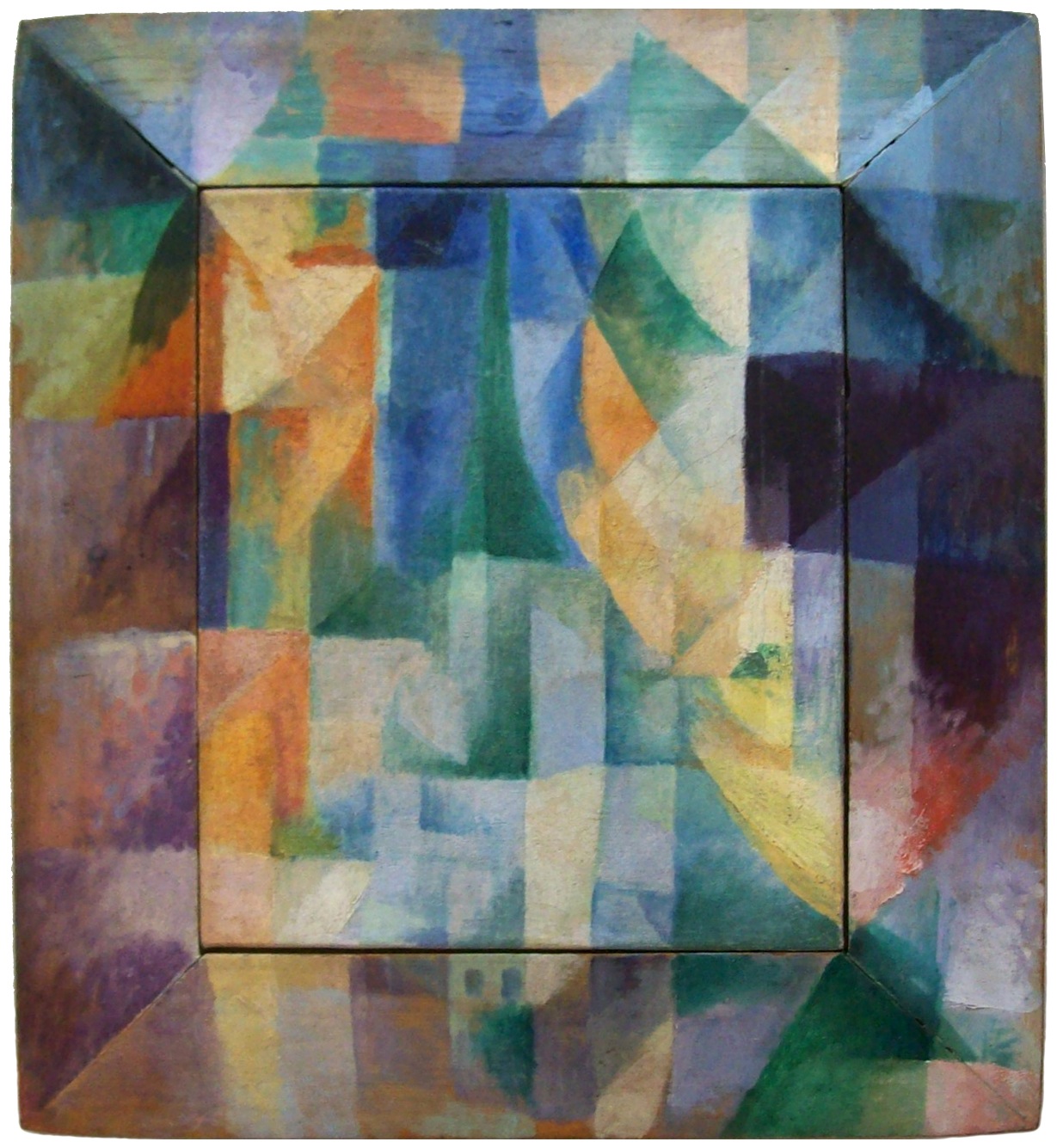

Windows Open Simultaneously (First Part, Second Motif) (1912) by Robert Delaunay

Multiple views overlap as if seen at the same time. Color replaces line as the main organizing force. The window becomes a metaphor for perception in the modern age. Space feels open, vibrating, and in constant motion.

The Bibémus Quarry (circa 1895) by Paul Cézanne

This landscape reduces nature to blocks of color and solid planes. Depth emerges through structure rather than traditional perspective. Cézanne does not fragment the scene, but he questions how form holds together. The painting stands at the threshold between Post-Impressionism and Cubism, showing how analysis of nature could lead to abstraction.

Source of the images: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain licence