Impressionism was a significant turning point in the art world, bursting onto the scene in late 19th-century France. Departing from traditional techniques, Impressionist artists sought to capture fleeting moments and the interplay of light and color in their work. Their paintings often appeared unfinished upon close examination, yet revealed remarkable detail and emotion from a distance. Curiously, Impressionism is often confused with Expressionism, yet the two are profoundly different.

Outstanding Impressionist Artworks

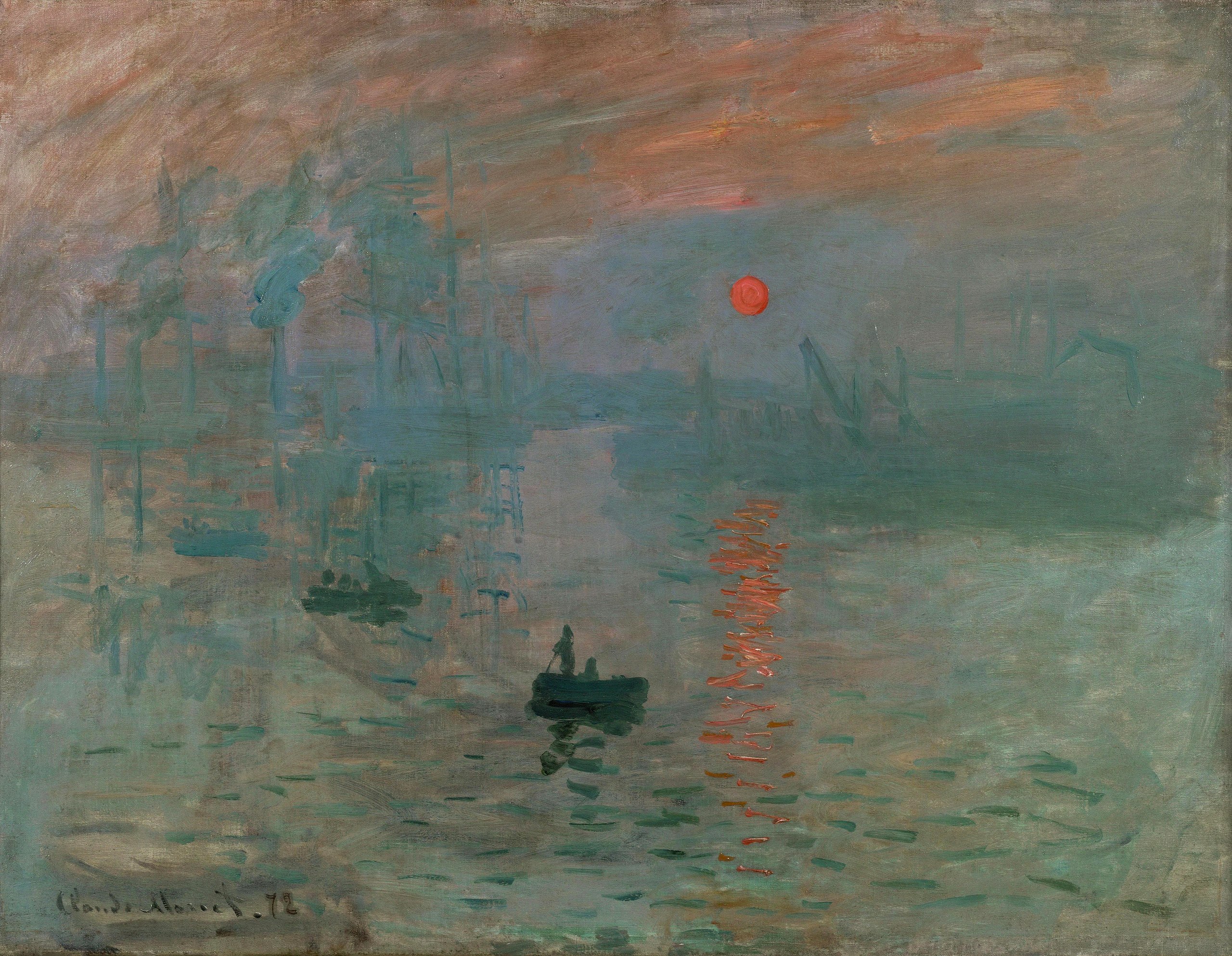

Impression, Sunrise (1872) by Claude Monet

When Monet painted this misty harbor, he had no idea he was naming an entire art movement. A critic mocked the work as a mere “impression,” and the name stuck. Instead of sharp detail, Monet gives us atmosphere — water, light, and air blending together. What matters here is not the port itself, but the fleeting moment of seeing it.

Starry Night on the Rhône (1888) by Vincent van Gogh

Unlike his more famous starry sky, this scene was painted outdoors, at night, directly from observation. Van Gogh watches gas lamps shimmer across the river, turning modern city light into something almost poetic. Thick paint and strong color make the night feel alive. The scene feels quiet, but emotionally charged.

Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–1881) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

This is not a staged scene; many of the people here were Renoir’s friends, enjoying a real afternoon by the river. Light moves across faces, glasses, and tablecloths, tying everyone together. There is no main character, only shared presence. Renoir captures leisure as warmth, conversation, and easy companionship.

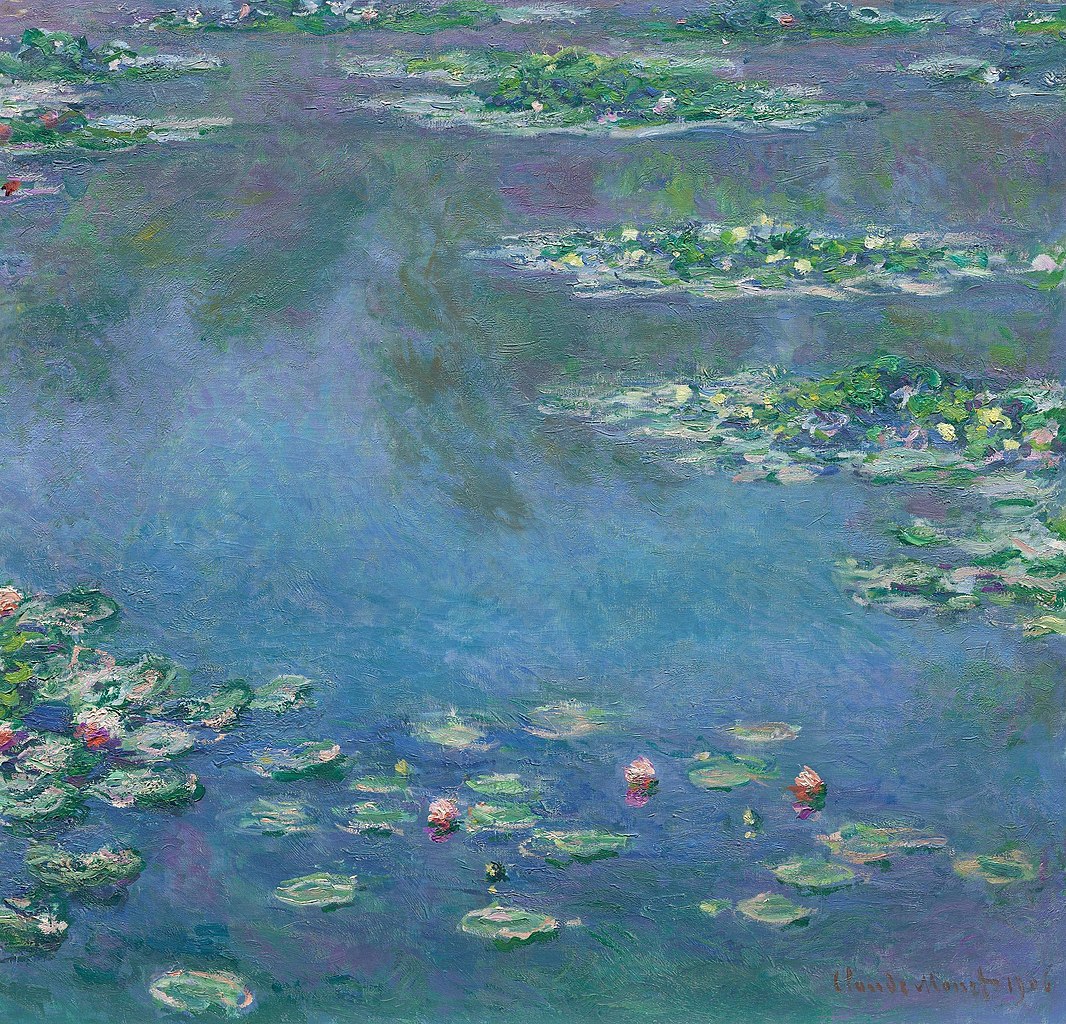

Water Lilies (1906) by Claude Monet

These paintings come from Monet’s own garden at Giverny, which he designed specifically to paint. There is no horizon, no sky — just water, reflections, and color. Standing before them, you lose a sense of direction. Monet invites you to experience looking itself, not a landscape.

The Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897) by Camille Pissarro

Pissarro painted this same street again and again, under different conditions. Here, artificial light fills the night with movement. Carriages, pedestrians, and glowing windows create a rhythm. The city feels alive, constantly shifting, never still.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) by Édouard Manet

At first glance, this looks straightforward — a barmaid at work. But the mirror behind her complicates everything. Reflections do not quite align, and the viewer’s position feels uncertain. The painting captures the loneliness that can exist inside public entertainment.

Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877) by Gustave Caillebotte

This scene shows modern Paris after its redesign: wide streets, clean lines, careful order. Yet people pass each other without connection. Umbrellas create distance. Caillebotte presents the modern city as impressive, but emotionally cool.

La Cathédrale (1908) by Auguste Rodin

Rodin does not fully define the cathedral’s form; instead, he lets light do the work. The surface appears rough and incomplete, as if the building were emerging from stone. This approach brings Impressionist ideas into sculpture. What we see changes as we move around it.

Spanish Dancer (Second State) (1920) by Edgar Degas

Degas was fascinated by movement, not perfect poses. This figure feels caught mid-motion, almost unstable. The surface remains rough, as though the artist stopped at the moment of energy rather than polish. Dance here is effort, discipline, and repetition rather than elegance.

Source of the images: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain licence