Symbolism (late 19th century) turns away from visible reality and looks inward, toward dreams, fears, myths, and ideas that cannot be observed directly. Instead of explaining the world, Symbolist artists suggest meanings through images loaded with metaphor and ambiguity. Literature, mythology, religion, and psychology all shape this movement. Color, line, and subject matter serve emotion and imagination rather than accuracy. What matters most is not what is shown, but what it implies.

Outstanding Symbolist Artworks

Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle (1872) by Arnold Böcklin

Böcklin places himself beside Death, who plays a fiddle close to his ear. The scene feels calm rather than terrifying, as if mortality were a constant companion rather than a sudden threat. Art becomes an act performed under Death’s watchful presence. The painting suggests that creativity and awareness of death exist side by side.

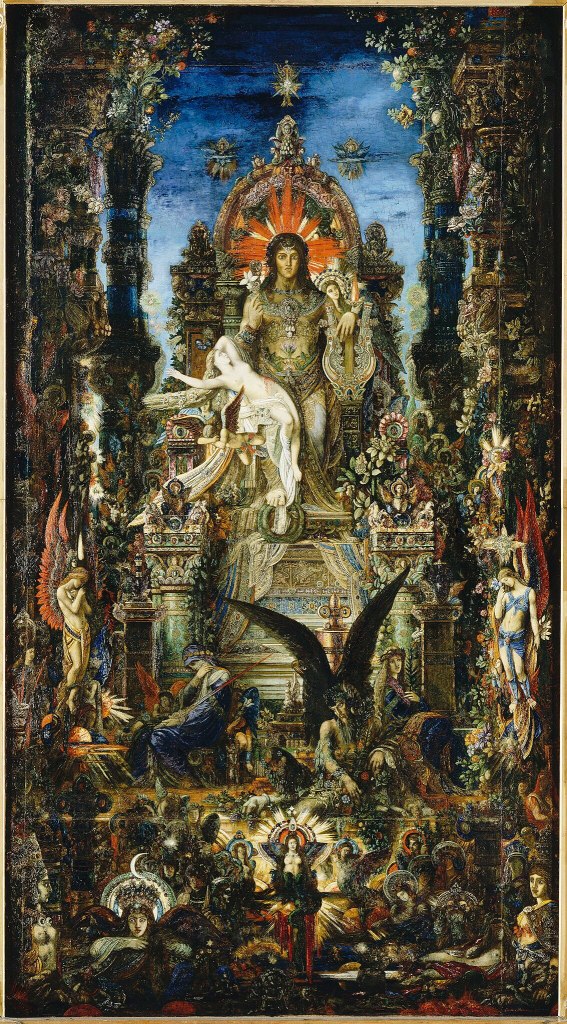

Jupiter and Semele (1894–1895) by Gustave Moreau

Moreau turns a classical myth into a vision dense with detail and symbolism. The scene overwhelms the eye with jewels, textures, and sacred motifs. Divine power appears intoxicating and destructive rather than heroic. Myth here becomes a vehicle for exploring desire, excess, and spiritual annihilation.

The Cyclops (c. 1914) by Odilon Redon

Redon presents the monster not as a threat, but as a quiet observer. The cyclops gazes gently at the sleeping nymph, suspended between tenderness and danger. Dream logic replaces narrative clarity. The image feels like a thought or vision rather than a scene from the real world.

The Sin (1893) by Franz von Stuck

A female figure emerges from darkness, entwined with a serpent. The painting draws on biblical and mythological imagery to link desire with temptation and danger. Stark contrasts and simplified forms give the scene a hypnotic intensity. Sin appears seductive, silent, and inevitable.

Caresses (1896) by Fernand Khnopff

A human figure meets a leopard-like sphinx in an intimate, unsettling encounter. The image resists clear interpretation; it balances attraction and threat. Khnopff avoids action or explanation, leaving the moment suspended. Desire becomes psychological rather than physical.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888) by James Ensor

Ensor transforms a sacred event into a chaotic modern spectacle. Christ almost disappears amid grotesque masks, banners, and shouting crowds. Religion, politics, and satire collide in a carnival-like procession. The painting questions sincerity, faith, and the place of the individual within mass society.

Source of the images: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain licence