Art movements have evolved throughout history as responses to cultural, social, and political shifts. Studying these movements is akin to assembling a vast jigsaw puzzle, where some pieces effortlessly come together, while others demand more careful attention. We’ve gathered this puzzle for you into a concise art history timeline, highlighting the significance of all art movements over time. Beyond a comprehensive overview, you will form associations with each art movement. This way, a bundle of dates, names, and styles will transform into memorable connections.

Here is a short PDF guide to major art periods and movements within them. Be sure to download it to keep it handy as you explore art further.

Shared Features of All Art Movements

An art movement is a collection of features characterizing a specific period of art history. Art movements often form under the influence of social circumstances and cultural inclinations, shaping the concepts, motifs, and innovations introduced in art.

An art movement has much in common with an art style; however, these notions are not interchangeable. While an art style implies a range of techniques and themes defining artworks by specific artists, an art movement encompasses art styles, ideologies, and artists based on shared characteristics of a certain period.

All art movements share the following features.

- Historical context

- Collective identity

- Reaction to previous art movements

- Ideology

- Art styles and techniques

The following art history timeline is a helpful tool to track how all art movements developed and interacted. We will begin at the very origins of art.

Ancient Art Features

Art, not as a notion but as beautiful physical things crafted by people, started thousands of years ago. The need for beauty is timeless. In his magnificent research work on art, Art as Experience, John Dewey wrote:

“Domestic utensils, furnishings of tent and house, rugs, mats, jars, pots, bows, spears, were wrought with such delighted care that today we hunt them out and give them places of honor in our art museums. Yet in their own time and place, such things were enhancements of the processes of everyday life.”

Regardless of the lack of artistic education and materials, the creative people of ancient times found ways to design and craft sophisticated wall prints, grand sculptures, and intricate architecture. The long-liveness of these artworks confirms how solid and well-constructed they are.

Ancient art dates back around 6000-3000 BCE to 400-600 CE. Different ancient cultures developed unique artistic traditions, reflecting their beliefs, values, and societal structures. Here are several general features of ancient art observed across various ancient civilizations.

- Symbolism and Ritual. Ancient art often served symbolic and ritualistic purposes. Artworks frequently depicted religious beliefs, myths, and rituals, acting as visual representations of the culture’s spiritual and ceremonial practices. What’s more, colors and materials in ancient art were often chosen for their symbolic significance.

- Human Figures. Ancient artworks often portray people in various activities such as hunting, farming, or participating in religious ceremonies. These figures were often idealized, reflecting cultural values and aesthetic ideals.

- Emphasis on Craftsmanship. Whether it was carving in stone, casting in bronze, or painting on pottery, the level of skill and precision exhibited in ancient artworks highlights the importance of craftsmanship in these societies.

- Monumental Architecture. Ancient cultures created impressive monumental architecture, including temples, pyramids, ziggurats, and amphitheaters. They were often constructed with religious or civic significance and showcased the engineering and architectural prowess of the civilization.

- Connection to Nature. Ancient art frequently drew inspiration from the natural world. Animals, plants, and natural elements often appeared in various forms, representing the close connection between ancient societies and their environments.

- Cuneiform Writing and Hieroglyphs. In several ancient civilizations, writing systems were incorporated into art. The cuneiform script in Mesopotamia and hieroglyphs in ancient Egypt, for example, were often integrated into reliefs and inscriptions.

Medieval Art Movements

During the Medieval period, art underwent significant changes, shifting from the symbolic imagery of Byzantine icons to the awe-inspiring grandeur of Gothic architecture. These shifts mirrored the evolving spiritual and social landscape of the time.

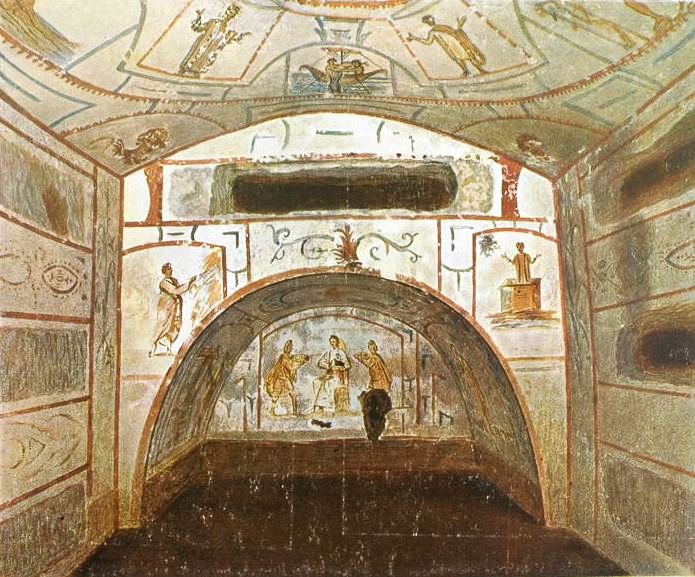

Early Christian Art

The first Christians created Early Christian art during the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. The emergence of Christian art was hugely motivated by the Greco-Roman culture involving vast visual arts. The newly converted Christians from Greece and Rome continued this artistic tradition and celebrated their new religion in frescos, murals, and illuminated manuscripts. Early Christian basilicas, adapted from Roman public buildings, became the primary architectural form for Christian worship.

Migration Period Art

After the fall of the Roman Empire (486 AD), European tribes massively migrated into its previous territories. The ethnic diversity produced dynamic cultural exchanges forming a blend of artistic practices of Germans, Huns, Franks, Goths, Slavs, Bulgars, and other European peoples. Migration Period artworks incorporated elements from the Roman Empire and showcased a dynamic fusion of pagan and Christian motifs. Notable features include intricate metalwork, showcasing detailed craftsmanship and often adorned with animal themes.

Byzantine Art

Byzantine art style emerged in the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, and pushed its boundaries towards other Christian countries. As a result, it combined Christian themes, Greco-Roman traditions, and artistic elements derived from East Syria, Persia, Egypt, and Asia Minor.

Insular Art

Insular Art refers to the artistic traditions of the British Isles and Ireland during the early medieval period (6th-9th c.). It is characterized by a unique fusion of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Christian influences. The distinguished features of Insular art include the preference for abstract over figural ornament, and for linear and rhythmic patterns over three-dimensional perspective.

Romanesque Art

The Romanesque (“in the manner of Romans”) period revived artistic forms inspired by Roman antiquity. While the term “Romanesque” was introduced in the early nineteenth century, the period spanned from roughly the 11th to the 12th century in Western Europe. Romanesque art witnessed the construction of massive stone churches and cathedrals, often with rounded arches, thick walls, and barrel vaults. Romanesque frescoes and murals adorned the interiors of churches, depicting religious themes and stories. The style laid the groundwork for the later Gothic period in medieval art and architecture.

Gothic Art

When the Dark Ages (5th-10th c.) were behind, the 12th century Europe witnessed economic growth, religious fervor, political stability, intellectual revival, and technological advancements, collectively influencing the artistic developments of the time. Gothic art shifted towards more intricate and vertical compositions, emphasizing light, space, and a sense of spiritual transcendence. Stained glass windows, like those in Chartres Cathedral, flood interiors with colored light. Sculptures displayed increased naturalism and emotion. Gothic art extended to illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings, reflecting a blend of religious themes and secular subjects.

Pre-Modern Art Movements

Art during the pre-modern era evolved due to cultural shifts like the Renaissance’s revival of classical ideals, religious influences on Baroque art, and technological advancements, all of which spurred innovation and experimentation in artistic expression.

Renaissance

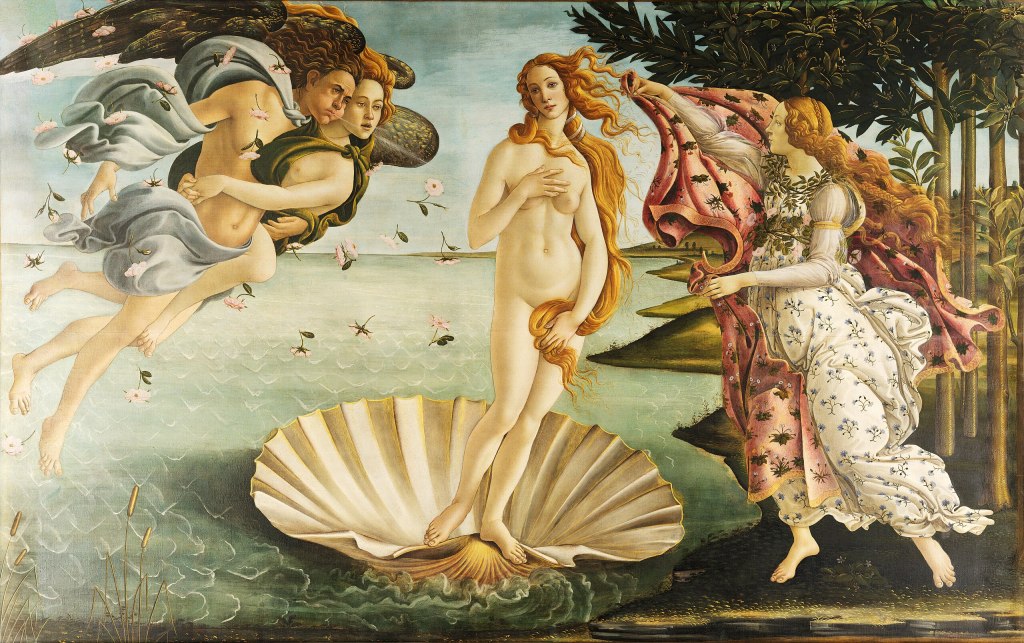

The late Gothic period was marked by significant shifts in artistic styles, philosophies, and cultural attitudes. Increased interest in humanism, classical antiquity, and Roman and Greek ideals fostered the transition to the Renaissance (14th-17th c.).

The Renaissance represents a defining moment in the art history timeline. Renaissance artists portrayed the world with greater realism and naturalism using techniques such as chiaroscuro (light and shadow) and linear perspective to create depth and three-dimensionality. Detailed studies of anatomy resulted in more accurate depictions of the human body. Renaissance architecture reflected classical aesthetic principles, with a focus on symmetry, proportion, and the use of classical orders. This period focused on harmony and human-centered design, shaping architectural styles for centuries.

Renaissance artists believed in the importance of the individual, so portraiture was a significant genre. There was also a notable increase in secular subject matter. Mythology, historical events, and scenes from daily life became popular subjects for paintings and sculptures.

Baroque

The historical events of the Baroque period (17th c.), including the Catholic Counter-Reformation, the Thirty Years’ War, the Scientific Revolution, and the rise of absolute monarchies, collectively influenced the themes, styles, and emotional intensity of Baroque art.

Baroque artists aimed for emotional intensity and realism. They depicted subjects with heightened emotions, capturing moments of extreme joy, sorrow, or tension. Tenebrism, an extreme form of chiaroscuro, emphasized deep shadows and bright highlights. Scenes from classical mythology were portrayed with the same emotional intensity as in religious works.

Baroque art embraced grandeur and ornamentation. Elaborate decorations, opulent materials, and intricate details reflected the wealth and power of the Catholic Church and aristocracy. Baroque artists, such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Peter Paul Rubens, created impressive ceiling frescoes and murals that adorned the interiors of churches and palaces, enveloping viewers in a multisensory experience.

Baroque art represented a departure from the restrained classicism of the Renaissance, embracing a dynamic and emotional aesthetic.

Rococo

Rococo art (18th c.) emerged as a reaction to the grandiosity of the Baroque period, bringing in its ornate and playful aesthetic, emphasizing elegance, lightness, and grace. This period coincided with the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement that valued reason, wit, and refinement. Rococo art reflected these ideals, often incorporating wit, satire, and a light-hearted approach to serious subjects.

Rococo style favored delicate and refined compositions, often featuring curved lines and asymmetrical designs. Intricate floral motifs, scrollwork, and delicate arabesques adorned paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts. Rococo often depicted domestic and intimate scenes of aristocratic life, emphasizing a departure from the monumental and religious themes of the Baroque. Artists used soft pinks, blues, greens, and lavenders to create a light and airy atmosphere in both paintings and interior design.

Rococo art flourished in the salons and drawing rooms of the aristocracy, reflecting the tastes and values of the 18th-century elite.

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism emerged in the late 18th century, opposing the ornate and playful style of Rococo and the extravagances of the Baroque. It drew inspiration from the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome, seeking to revive classical ideals.

Neoclassical art emphasized rationality, order, and a return to reason, reflecting the influence of Enlightenment ideals. Idealized and balanced forms embraced symmetry and proportion in their compositions, while limited colors and muted tones conveyed a sense of seriousness and clarity. Portraits often depicted individuals in classical clothing, connecting them to the ideals of antiquity.

Besides historical themes and heroic subjects, Neoclassical art was often infused with moral and civic messages. Artists aimed to inspire virtue, patriotism, and a sense of duty, reflecting the social and political aspirations of the time.

Romanticism

Romanticism emerged as an influential artistic and intellectual movement in the late 18th to mid-19th century, reacting against the rationalism of the Enlightenment and the constraints of Neoclassicism.

Romanticism embraced spontaneity, intuition, and subjective experience. Nature held a central place in Romantic art and served as a metaphor for emotional states and the human experience. Artists found inspiration in landscapes, sublime scenes, and the untamed beauty of the natural world.

The period of Romanticism played a role in fostering nationalism and a sense of cultural identity. Artists explored folklore, mythology, and historical themes to connect with the cultural roots of their nations. Criticizing the Industrial Revolution, they often looked to the past with a sense of nostalgia. Medieval and Gothic themes were romanticized, emphasizing a perceived simplicity, chivalry, and connection to nature.

Realism

Realism (mid-19th c.) sought to depict the world objectively and truthfully, without idealization. Rather than turning to historical or mythological themes, artists focused on the meticulous portrayal of ordinary, everyday subjects. Scenes from urban life, rural landscapes, and the daily struggles of common people often carried a social critique, addressing issues such as poverty, inequality, and the harsh realities of life.

The emergence of photography fostered realistic representation of everyday scenes. The play of light and shadow, the capture of random moments, and the expansion of subject matter all reflected the impact of photography on Realism.

Modern Art Movements (Pre-World War)

Modern art movements before World War I embraced innovative techniques and subjective interpretations. Modernists challenged traditional artistic conventions and paved the way for further experimentation in the 20th century. Many major modern art movements, such as Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism, remain highly influential and popular today.

Impressionism

Impressionism emerged in France in the late 19th century, around the 1860s to 1870s. It moved away from traditional artistic conventions, emphasizing the artist’s perception and immediate impression of a scene over realistic representation.

Impressionist artists tried to capture the effects of light and atmosphere in their paintings. Color became a crucial element. The use of bright, pure colors, accompanied by the effects of juxtaposition, created vibrant and dynamic compositions. Artists often painted outdoors–en plein air–to observe and depict the changing qualities of light throughout the day. The ordinary scenes of modernity and the effects of industrialization were common themes in Impressionist artworks.

Impressionists rejected the meticulous detail of academic painting. Instead, they relied on the viewer’s perception and interpretation. Their brushwork was loose with visible strokes compared to the smooth and blended brushwork of academic painting.

Post-Impressionism

While sharing some characteristics with Impressionism, Post-Impressionism (late 19th – early 20th c.) moved beyond its limitations and explored new directions in color, form, and expression. It encompassed a diverse range of individual styles, and each artist within the movement developed a distinctive approach.

Post-Impressionists placed a greater emphasis on symbolism and subjectivity. They aimed to convey emotions, ideas, and personal interpretations of reality, moving beyond the purely observational and objective approach of Impressionism. They often introduced more structured compositions compared to the spontaneous and loose compositions of Impressionism. Paul Cézanne, in particular, focused on the geometric and underlying structure of forms, contributing to the development of Cubism.

Symbolism

Symbolism (late 19th – early 20th c.) was an artistic and literary movement that expressed complex ideas and emotions through symbolic imagery, often exploring themes of the mystical, the dreamlike, and the subconscious. This movement arose as a reaction against the perceived limitations of Realism and Naturalism. Instead of depicting the external world with objective accuracy, Symbolist artists focused on inner experiences, emotions, and subjective realities.

Symbolists often adopted synesthesia, blending different sensory experiences in their works. They aspired to create a “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk) combining visual art, literature, music, and other forms to evoke a comprehensive emotional response. They often drew inspiration from mythology, folklore, and archetypal symbols.

While Symbolism as a distinct movement declined in the early 20th century, its impact endured, leaving a lasting imprint on the evolution of modern art.

Fauvism

The term “Fauvism” comes from the French word “les Fauves,” meaning “the wild beasts,” and it was coined due to the movement’s bold use of color and energetic brushwork. It emerged around 1905 and lasted until about 1910.

Fauvism artists often used non-naturalistic colors, often applied directly from a tube, this way expressing their emotions and perceptions. Objects and figures were simplified and exaggerated indicating a more liberated and subjective approach to art.

While it was a short-lived movement, Fauvism played a crucial role in challenging artistic conventions and pushing the boundaries of color and form in painting.

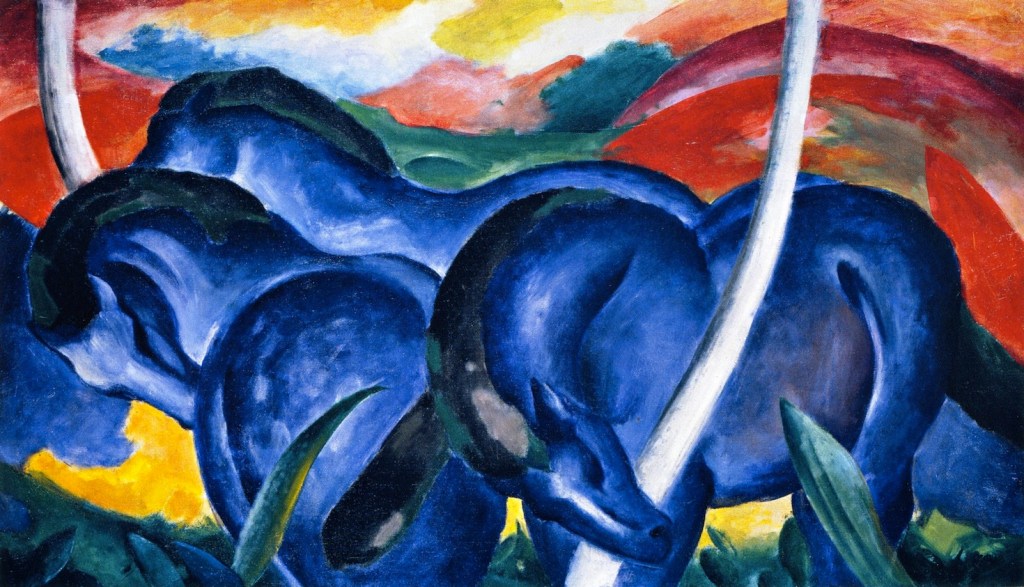

Expressionism

Expressionism emerged in the early 20th century, particularly in the years leading up to World War I. This movement focused on subjective emotions, distorted forms, and a departure from realistic representation.

Expressionist artists attempted to evoke powerful feelings and explore the inner experiences of the human psyche, frequently using bold colors and dynamic brushwork. Dreams, nightmares, and fantastical elements often appeared in their works.

Some Expressionist works carried a social or political critique, reflecting the turbulent times in which the movement emerged. Themes of isolation, alienation, and the individual’s struggle with modern society were common. Artists depicted the emotional toll of industrialization, urbanization, and war.

Cubism

Cubism was a revolutionary art movement that emerged around 1907-1908 and introduced a radical approach to depicting space, form, and objects.

Cubists broke their objects down into geometric shapes, particularly cubes, and abstractly reassembled them. Aiming to represent objects and figures from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, they depicted different facets of an object within a single composition. Losing the illusion of three-dimensional space, Cubist paintings often featured flat, fragmented surfaces rather than traditional depth.

Cubism had a profound impact on subsequent movements such as Futurism, Constructivism, and even aspects of Surrealism.

Futurism

Futurism started in Italy in 1909, led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It focused on modern life, machines, and movement, celebrating the energy of cities, cars, and industry. Artists tried to show motion and speed in painting, sculpture, and even poetry, using new shapes and forms. They were influenced by Cubism but wanted their art to feel alive and active, not just a study of form. Futurism also challenged traditional ideas about art, often rejecting the past, and aimed to create work that reflected the fast-changing modern world. Some Futurists were involved in theater, music, and design, spreading their ideas beyond visual art.

Post-Modern Movements

Post–Modern art movements arose in reaction to the disillusionment and upheaval of World War I. They embodied experimentation, irrationality, and social critique in their artistic expressions.

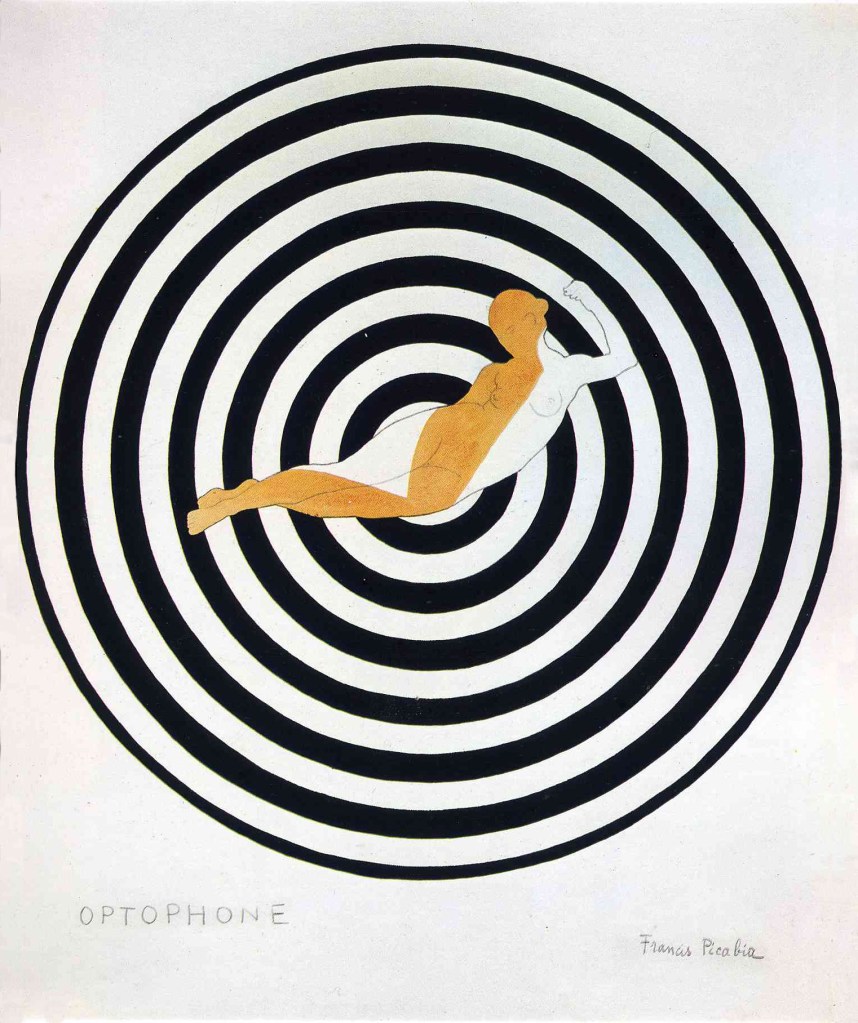

Dadaism

Dadaism was an avant-garde art movement that emerged during World War I, primarily in Zurich, Switzerland, and later spread to other European cities. It rejected traditional artistic conventions, embracing absurdity, anti-art sentiments, and a strong critique of societal norms.

Dadaists created artworks that often incorporated found objects (“readymades”), collage techniques, and performance art. They tried to disrupt established cultural and artistic norms, reflecting a response to the disillusionment and chaos of the war years. Dadaism had a significant impact on the development of conceptual art and influenced subsequent avant-garde movements.

Surrealism

Surrealism was founded by French writer and poet André Breton in the early 1920s. Surrealism artists explored the irrational and subconscious aspects of the human mind. They applied dreamlike imagery and fantastical elements to create art that transcended reality. Also, they used automatic techniques, such as automatic writing and spontaneous drawing, to bypass conscious control and access the subconscious mind.

The Surrealism movement extended beyond visual arts to literature, film, and philosophy, influencing a wide range of cultural fields.

Bauhaus

Bauhaus was a revolutionary art and design school founded in Germany in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius. Active until 1933, when it was closed by the Nazis, Bauhaus sought to unite fine arts, crafts, and technology in a holistic approach to design education. The school emphasized functionalism, simplicity, and the integration of art with industry. Bauhaus profoundly influenced modern architecture, design, and education, promoting a harmonious union of aesthetics and utility.

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism (1940s–1950s, mainly in the U.S.) evolved from Expressionism but took it further by removing recognizable subjects entirely. Instead of depicting figures or scenes, these artists used spontaneous gestures, large-scale canvases, and non-representational forms to express emotions. It was more about process and movement, as seen in Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings or Mark Rothko’s color fields.

Artists like Willem de Kooning blended abstraction with the human figure, using aggressive brushstrokes to capture raw energy. Their work was met with both awe and confusion, but it reshaped the art world, shifting its center from Paris to New York. For the Abstract Expressionists, art was no longer about representation, but about pure, instinctive expression, forever changing the way we experience painting.

Pop Art

In the 1950s and 1960s, as televisions flickered in every home and advertisements filled the streets, a new art movement emerged that celebrated—and mocked—modern consumer culture. Pop Art was loud, colorful, and unapologetically tied to mass media. It rejected the seriousness of Abstract Expressionism, instead embracing the everyday world of comic strips, celebrities, and brand logos. Andy Warhol, one of its most famous figures, turned Campbell’s soup cans and Marilyn Monroe’s face into iconic art, blurring the line between high art and commercial imagery.

Meanwhile, Roy Lichtenstein transformed comic book panels into massive paintings, mimicking cheap printing techniques with hand-painted dots. Artists like Claes Oldenburg made giant sculptures of everyday objects, like hamburgers, typewriters, lipsticks, turning the ordinary into the extraordinary. Pop Art was playful but subversive, questioning the role of consumerism, media, and fame in modern life. By making art that felt mass-produced, it forced people to reconsider what art could be and who it was for.

Read more about post-war art movements in Post-War Art and Culture: Europe & The United States.

Need more visualisation? Complete your research by studying examples of major art movements in Artenquire’s gallery.